Building Reliable AI Agents

AI agents accomplish a task in a mostly unstructured manner – where they are able to reason and conduct actions to achieve a goal. The key is in providing just enough structure through tool design, harness design, and context engineering to guide the agent effectively.

I got interested in agents around September 2023 and started by prototyping with gpt-3.5 and gpt-4. We’ve come a long way since then, but the fundamentals remain the same. Approaching building these from first principles – similar to how software engineering often needs to be approached – is the best way to build agents which work well.

Last year, around January 2024, I started my own company called Extensible AI where we worked on agent reliability, frameworks, and applications. It was probably a bit too early to work on agent reliability but it taught me a lot about what worked and didn’t work when it came to building agents.

Don’t be fooled, building agents well is still rooted in the same principles of software engineering. Software is often decomposed as Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs). Agents take parts of this software and make it into a black box, where the DAG is generated by the model to go from a goal to an action in a loop. I personally like the DAG idea quite a bit – so much so I built DAGent last year to deal with models not being as good with agentic tool use.

We’re at a point where we’re going to see more and more of this DAG being generated and executed by the model. 2026 will be where we need to do less and less targeted engineering work to get the model to execute a task correctly.

I’ll also focus more on open-source models as they’re wildly different from the start of the year, especially with the release of Kimi-K2, Minimax M2.1, GLM-4.7, and Qwen3-coder. A lot of my personal workload for coding has shifted to these models. I think they’re well suited for 90% of tasks at this point. Depending on your use case, some open source models might even be better picks than closed-source models.

Anatomy of an agent

Models like Kimi-K2, Minimax M2.1, GLM-4.7, and Qwen3-coder tend to perform well in an agent loop. These models have an understanding of how to use tools they are provided and are able to go from a provided goal to conducting actions to reach that goal

The simplest way to build an agent with capable models is to throw it into a loop with a goal and a set of tools. The following diagram shows the agent execution loop:

Diagram: Agent execution flow - the model continuously generates responses and executes tools until the goal is reached.

graph TD

A[Start: Goal + Message History] --> B[Model generates response]

B --> C{Tool calls?}

C -->|Yes| D[Execute tool]

D --> E[Add result to history]

E --> B

C -->|No| F[Reached goal. Print response]

F --> G[End]

style A fill:#e2d9c9

style G fill:#e2d9c9

style B fill:#f6f2e8

style C fill:#f6f2e8

style D fill:#f6f2e8

style E fill:#f6f2e8

style F fill:#f6f2e8

Code: Minimal agent loop pseudocode - this shows the core pattern: generate response, check for tool calls, execute tools, repeat until done.

goal = "do x for me"

message_history = [goal]

while true:

response = model.generate(message_history, available_tools)

message_history.append(response)

if response.tool_calls:

result = execute_tool(tool_calls)

message_history.append(result)

else:

print(response)

break

Under the hood, the model is in a feedback loop, much like a controls system. The model is trying to reach a set goal by conducting actions, and trying to minimize the error between the goal and the action.

Agents as control systems and policies

Note: This section is optional and covers some more of the theoretical thoughts behind how agentic models get trained. Insightful but not necessary for building agents.

From a control theory perspective, the agent is minimizing an error function at each step:

$$e(t) = \text{distance}(\text{goal}, \text{current state})$$

The model selects actions to minimize $\sum_{t} e(t)$ over the trajectory, similar to how a PID controller works to reach some steady state.

From a reinforcement learning perspective, this loop is executing a policy $\pi(a|s)$ where:

- State (s): Current message history + goal

- Action (a): Tool calls or final response

- Policy (\pi): The LLM itself, generating actions given the state

The policy can be expressed as:

$$\pi(a|s) = P(\text{action} \mid \text{state})$$

where the model learns to maximize expected reward over trajectories:

$$\max_{\pi} \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi} \left[ \sum_{t} r(s_t, a_t) \right]$$

where:

- $\tau$ is a trajectory which is a sequence of states and actions

- $r(s_t, a_t)$ is the reward function at time $t$ for taking action $a_t$ in state $s_t$

- $\mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi}$ is the expected value over all trajectories generated by policy $\pi$

Thinking of these behaviours in terms of control systems and policies means that this behaviour can be trained and optimized through RL. Modern models are increasingly post-trained using policy optimization methods like GRPO — Group Relative Policy Optimization — and PPO — Proximal Policy Optimization — for agent tasks.

I recommend the following video by Yacine: Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) - Formula and Code

The training process typically involves:

- Running the agent through many task trajectories

- Comparing outcomes using reward signals - task completion, efficiency, tool usage quality

- Using the relative performance to fine-tune the policy

This is where the harness becomes critical. The harness - the specific tools, system prompts, and execution environment used during training shapes how the model behaves as an agent given an environment to take actions in. A model trained on a Codex-style harness will naturally exhibit different tool-calling patterns than one trained on an Claude code style of harness.

As models get better, we’re seeing more targeted post-training for specific harnesses. GPT-5.2-Codex is optimized for the Cursor/Codex CLI environment. Claude is optimized for MCP and their code environment. The harness is now a critical part of the model’s learned behaviours.

Building a simple agent

Here is a simple agent which uses a tool to search the web and then summarize the results:

Code: Complete web search agent - a working example with comments showing initialization, the main loop, tool execution, and result handling. Main callout here is that the tool outputs are truncated to 2000 tokens for context window management.

# Define the goal

query = "who is parth sareen"

print('Query:', query)

# Initialize message history with system prompt and user goal

# System prompt defines agent behaviour and success criteria

messages = [

{'role': 'system', 'content': 'You are a pro at making web searches. You are free to make as many searches until you satisfy [x constraints]'},

{'role': 'user', 'content': query}

]

# Main agent loop

while True:

# Model generates response based on message history and available tools

response = chat(model='qwen3', messages=messages, tools=[web_search, web_fetch], think=True)

# Some models support thinking/reasoning before acting

if response.message.thinking:

print('Thinking:')

print(response.message.thinking + '\n\n')

if response.message.content:

print('Content:')

print(response.message.content + '\n')

# Add model's response to message history for context

messages.append(response.message)

# Check if model wants to use tools

if response.message.tool_calls:

for tool_call in response.message.tool_calls:

function_to_call = available_tools.get(tool_call.function.name)

if function_to_call:

# Execute the tool with model's arguments

args = tool_call.function.arguments

result = function_to_call(**args)

print('Result from tool call:', tool_call.function.name)

print(args)

print(result)

print()

# Add tool result to history (truncated to ~2000 tokens for efficiency)

messages.append({'role': 'tool', 'content': result[:2000 * 4], 'tool_name': tool_call.function.name})

else:

print(f'Tool {tool_call.function.name} not found')

messages.append({'role': 'tool', 'content': f'Tool {tool_call.function.name} not found', 'tool_name': tool_call.function.name})

else:

# Model is satisfied and provided final answer without requesting tools

break

This example demonstrates the agent anatomy from earlier in practice. The agent loops until it’s satisfied with the search results, then provides a final answer.

System prompts

The system message plays a crucial role in guiding the agent’s behaviour and defining what it means to “satisfy a goal”. Some good examples to reference are:

The prompt often needs to be tailored to different models and how they work best in order to extract the most out of them.

Depending on your use case, you may also want to provide a rubric for your agent to reason about and grade its progress, enabling better decision-making.

Context engineering for agents

Tool Design

I’d argue that tool design is one of the most critical and overlooked aspects of building reliable agents. Engineers often add tools without considering what the model actually sees and reasons with when given instructions on how to solve a problem.

Models are trained to consume tools in various different formats. While the input to most SDKs/APIs is a JSON schema for a tool, these are usually getting transformed into a different format which the model is trained on. This has been done through Jinja templates or Go templates for Ollama for the last couple years but it seems the industry is moving more towards renderers with code - see Thinky’s Tinker docs or Ollama’s renderers for examples.

The below is an example of tools JSON schema being passed into gpt-oss and the rendered prompt that the model actually sees.

Input tool schema: usually inputted as JSON, or some tools allow for direclty passing in the function definition.

{

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"get_location": {

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": "get_location",

"description": "Gets the location of the user.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {},

"required": []

}

}

},

"get_current_weather": {

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": "get_current_weather",

"description": "Gets the current weather in the provided location.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"location": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The city and state, e.g. San Francisco, CA"

},

"format": {

"type": "string",

"enum": ["celsius", "fahrenheit"],

"description": "Temperature format",

"default": "celsius"

}

},

"required": ["location"]

}

}

},

"get_multiple_weathers": {

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": "get_multiple_weathers",

"description": "Gets the current weather in the provided list of locations.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"locations": {

"type": "array",

"items": {

"type": "string"

},

"description": "List of city and state, e.g. [\"San Francisco, CA\", \"New York, NY\"]"

},

"format": {

"type": "string",

"enum": ["celsius", "fahrenheit"],

"description": "Temperature format",

"default": "celsius"

}

},

"required": ["locations"]

}

}

}

}

}

Rendered tool prompt: What gpt-oss actually sees - TypeScript-style function definitions in OpenAI’s Harmony format, showing how JSON schemas get transformed.

<|start|>system<|message|>You are ChatGPT, a large language model trained by OpenAI.

Knowledge cutoff: 2024-06

Current date: 2025-06-28

Reasoning: high

# Valid channels: analysis, commentary, final. Channel must be included for every message.

Calls to these tools must go to the commentary channel: 'functions'.<|end|><|start|>developer<|message|># Instructions

Use a friendly tone.

# Tools

## functions

namespace functions {

// Gets the location of the user.

type get_location = () => any;

// Gets the current weather in the provided location.

type get_current_weather = (_: {

// The city and state, e.g. San Francisco, CA

location: string,

format?: "celsius" | "fahrenheit", // default: celsius

}) => any;

// Gets the current weather in the provided list of locations.

type get_multiple_weathers = (_: {

// List of city and state, e.g. ["San Francisco, CA", "New York, NY"]

locations: string[],

format?: "celsius" | "fahrenheit", // default: celsius

}) => any;

} // namespace functions<|end|><|start|>user<|message|>What is the weather like in SF?<|end|><|start|>assistant<|channel|>analysis<|message|>Need to use function get_current_weather.<|end|><|start|>assistant<|channel|>commentary to=functions.get_current_weather <|constrain|>json<|message|>{"location":"San Francisco"}<|call|><|start|>functions.get_current_weather to=assistant<|channel|>commentary<|message|>{"sunny": true, "temperature": 20}<|end|><|start|>assistant

In this case, the model is trained to see the tools in a typescript-esque format and outputs tools in its own Harmony format.

The reason why this is important is that there could be a divergence in types from the JSON schema to the rendered prompt which could lead to sub-par tool usage by the model.

I recommend not having referenced or nested types as much, and sticking to simpler types which can later be cast as needed. It also helps to think about the pre-training and post-training of a model. Models have probably seen less nested JSON and fewer custom types in the training corpus than non-nested JSON. This also gets more complicated when there are custom formats that a model was trained on. The more layers of abstraction we add, the higher the likelihood that something is not getting rendered correctly. I’ve spent way too much time debugging whitespaces in a rendered prompt, trust me, you want to keep tool schemas simple. A single whitespace or newline can change the activations for a model; when it is part of the template the model was trained on, having it incorrect can change the model’s outputs drastically.

Similarly the tool output also needs to be parsed back into a JSON schema, and different providers may choose to parse in their own way depending on the inference engine they are using. Poor parsing by the provider can have two negative effects: it slowly degrades the model’s tool calling capabilities, and it breaks the KV cache since the re-rendered prompt would not match the original prompt + generated tokens.

Certain tools you build will require their own state management and storage – think updating memory about a user, project management, long-running tasks, etc. Providing these tools to the model while keeping their interface to the model simple is crucial to not overwhelm it.

Tool outputs

How you present tool results to the model significantly impacts agent performance. Consider both the format and the amount of information you return.

Limiting output size

In the web search example earlier, I cap results to ~2000 tokens. Search providers often return both a snippet and full page content, which can overflow the context with unnecessary information. Limiting token counts helps keep the agent focused on relevant data.

Instead of dumping all the information received from an API, clean it up and limit what you send to the model. This keeps the agent focused and efficient.

Understanding model expectations

Going a layer deeper to see what the model is trained on can help improve performance. Check if the model expects JSON, string, or a different format for its tool results and how the inference engine parses it.

The training of the model matters quite a bit - some models are post-trained to expect a certain format for tool results or have learned to call certain tools more effectively than others.

Model-specific behaviours

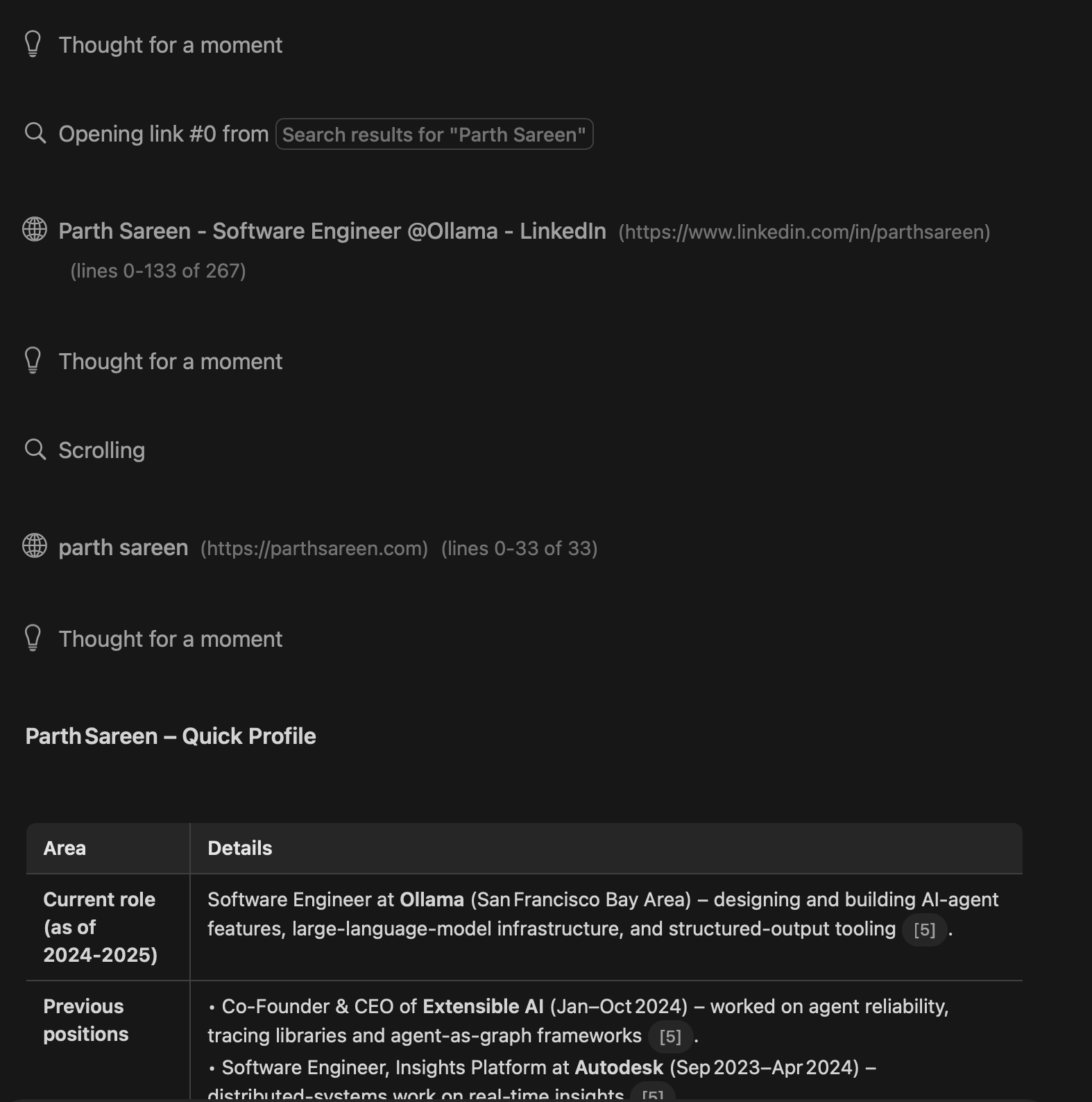

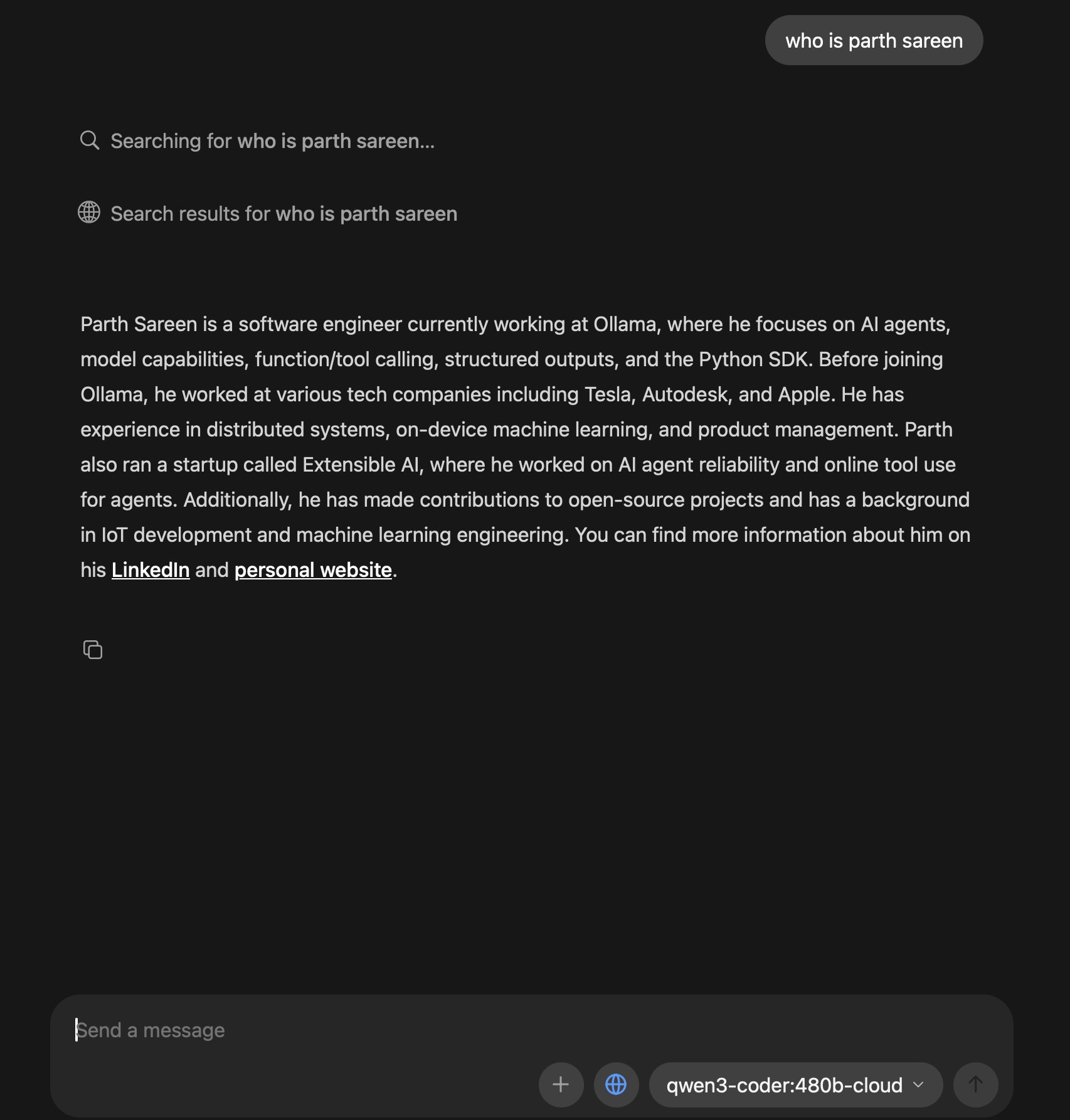

The following examples show how different models approach the same web search task differently:

In the above examples, gpt-oss:20b is able to perform multiple searches, fetch content, and even search within a page for terms due to the tools it was trained on. I’d consider this to be a part of the agent harness of the model.

On the other hand, qwen3-coder:480b – which is a much bigger model, only makes a cursory search and pre-emptively returns the result due to being satisfied with the result. There’s always going to be tradeoffs on training for specific tools and harnesses vs being a general purpose model.

It’s a pretty clear difference that trained model behaviours outperform untrained or generalized behaviours. Understanding the harnesses of the model and what they’re optimized for can give you an edge to build better agents.

How to know what information to give

Building effective agents is mostly about selecting which information to provide to the model. Just like a program execution flow, the model needs the right information at each step to successfully complete its task.

Overall, try to provide the most relevant information to the model without filling up too much of the context window. Depending on what kind of agent you’re building, you’ll need to be selective about what information to provide.

I’ve generally found that providing environmental context is most effective. The agent should be aware of:

- Its overall purpose and goals

- Where it’s operating

- Its limitations and capabilities

- Environmental information - date, time, current location

- User preferences and memory

- Available tools and their purposes

For example, a research agent would need search tools plus context about the user’s preferences, current date/time, and any relevant memory from past interactions.

Each model has different characteristics in how it approaches problems and uses tools. Building your own suite of benchmarks is necessary to evaluate which models work best for your specific use case. Based on how tool use is trained for the model, what kind of tools are provided to it, and what the environment is, different models will complete the same task differently, even if the end result is the same.

Data sources

Information is either retrieved in some manner - Database, API, Web Search, File search, etc. - or is provided to the agent in its chat history directly.

For example, if a user wants to continue planning a project, the agent needs:

- Memory of what was previously discussed

- Access to the project’s current state – via tools with their own state management

You can provide this context by either injecting it at conversation start, or by instructing the model through the system message to retrieve it from persistent storage.

Context compression

Context compression occurs when the agent is near its context window limit. The model is trained on some context length and often degrades steeply in performance after hitting that trained limit. This is essentially KV cache management for the model – strategies like YaRN extend the context length of a model by rescaling positional embeddings beyond the original training window. YaRN addresses the overall amount of information the model can see, but the performance still degrades for how well the model will remember the past information.

There are 2 main strategies for context compression:

- Summarizer - The summarizer is often a model that will look at (n) messages and summarize them into (m) messages.

- Sliding window - The oldest messages are removed as new messages are added. This is often defined by the inference provider and sometimes tunable.

A mix of the two strategies is recommended and often used in industry where the most recent messages are kept, while older messages are summarized to maintain overall context.

Benchmarking your harness over long running tasks is necessary to see what works best.

Benchmarking

With new models releasing every couple of weeks, having a reliable way to benchmark your agent is essential.

Your harness will perform differently across models, APIs, and providers. You need to define:

- What reproducible behaviours you want to test

- Success criteria

- Edge cases

Don’t overindex on public benchmarks. You need to think about what reproducible behaviours you want to capture and test for in your agent. See how you feel about different models with your agent harness.

Final thoughts

It’s best to build agents without too many frameworks and tools to begin with. Approach it from first principles and build or add frameworks as needed.

At the current rate of model progress, I expect most benchmarks to be outdated within a year.

Agent harnesses and post-training for those particular harnesses is something I had hypothesized around the launch of Claude code, but it’s starting to become more and more apparent. E.g. GPT-5.2-Codex focusing on tools built around Codex CLI and Cursor, and Claude Sonnet and Opus focusing on post-training with MCP and Claude code.

I think we’ll see a rise in specialized models for specific harnesses, as well as more generalized models which can fit anywhere but maybe not perform as well. You can also see that harnesses impact overall model output quite a bit. See Factory AI’s Droid.

I have some fun agent-heavy stuff in the works – both for Ollama and my own tools. Hope to share these soon :)